Henselmann, Architekt, Ost-Berlin – Biography and Epilogue

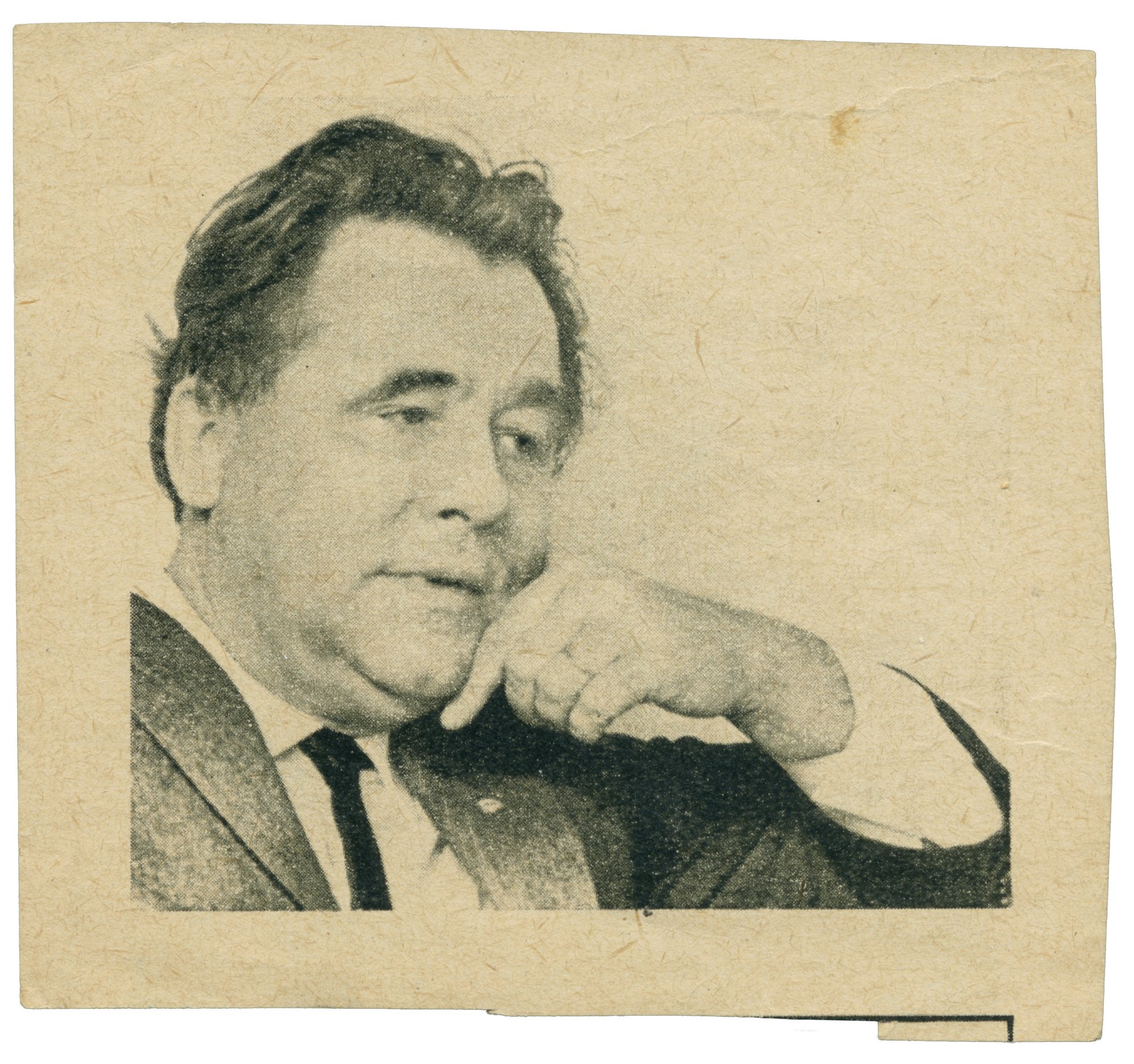

Hermann Henselmann

Born on 3 February 1905 in Roßla, a town in the South Harz region of Germany; grew up in Bernburg an der Saale.

Carpentry apprenticeship; study at Handwerker- und Kunstgewerbeschule Berlin (Berlin School of Applied Arts and Crafts)

1926–1930 Employed at the offices of architects Arnold Bruhn and Leo Nachtlicht.

1930 First independent commission as a collaboration with film architect Alexander Ferenczy: Villa Kenwin in Montreux, Switzerland. Subsequently, planning and completion of villas and standalone houses in Berlin and environs as a private architect.

During National Socialist rule, Henselmann gave up his independent status and took a position as architect for Carl Brodführer und Werner Issel, architects specialising in industrial construction; during the Second World War he served as an architect working on the reconstruction of destroyed farms in the Wartheland region, later as office manager for architect Godber Nissen.

1945 Stadtbaurat (head of city planning office) in Gotha.

1946 Director of Hochschule für Bauwesen (College of Architecture), Weimar.

1949 Head of Department at the Institut für Bauwesen der Deutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Civil Engineering Institute at the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin) in East Berlin.

1953–1959 Architect-in-chief at the East Berlin Magistrat (city council).

1959–1964 Architect-in-chief at the Institut für Sonderbauten der Bauakademie (Institute of Special Structures at the Academy of Architecture); to 1967 Director of the Institut für Typenprojektierung und industrielles Bauen (Institute of Type Projects and Industrial Construction).

1967–retirement in 1972 Deputy Director of the Institut für Städtebau und Architektur der Bauakademie (Institute of Urban Planning and Architecture at the Academy of Architecture).

Architectural works in East Berlin:

Hochhaus an der Weberwiese 1951/52

Strausberger Platz 1952–1955

Frankfurter Tor, design 1953, construction 1957–1960

Haus des Lehrers and Kongresshalle 1961–1964

Fernsehturm, design 1959, construction 1965–1969

Further important architectural works:

Hochhaus der Universität Leipzig, 1972

Hochhaus der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, 1972

Died 19 January 1995 in Berlin.

From Ruins to the Future

Florian Havemann

26 September 1954

In the meantime, I have seen a photograph of my successor for the eastern part of Berlin, Architect-in-Chief Henselmann, who designed Stalinallee. He was showing models of the city of Berlin to prestigious visitors, just as I once did. I have the impression that Stalinallee follows the course of the Ostdurchbruch, our planned road extending to the east. And the ring roads I had envisaged are being constructed in West Berlin. Perhaps at some stage a simpler version of the new Berlin South railway station may be built.

Albert Speer, Spandau Diaries

Everything that was built by this man, this Henselmann, this Hermann Henselmann, was based on a single premise: war.

His works of construction were the successor to works of destruction.

Henselmann can thank Adolf Hitler – who had himself had ambitions of being an architect – for the scope to design such large-scale buildings that shaped the cityscape of Berlin. That had been precisely Hitler’s intention: to completely reshape Berlin, with Albert Speer as his assistant. The plans had been drawn up, and the Great Hall was scheduled for completion in 1955. But the war ended ten years before that time, in 1945; the war started by the German, the Greater German Reich, the war that Hitler had wanted. The exiled Brecht, Bertolt Brecht, returning to Berlin in 1947, described the city as a “heap of ruins near Potsdam”.

Those ruins were the prerequisite for an architect of Henselmann’s stamp to be able to build on such a large scale. The space was there; all that was needed was to clear the rubble. And the need for housing was there: Henselmann’s first three projects in Berlin – the Hochhaus an der Weberwiese, Strausberger Platz, Frankfurter Tor – were all apartment blocks.

Let us never forget that Adolf Hitler invited the Red Army into Germany by invading the Soviet Union. A Socialist state was created out of part of Germany, the eastern part, but not by communists; it was the Big Three, Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin, who decided in Yalta to divide Germany up into occupied zones after the country’s unconditional capitulation. One of those zones was Berlin. Accompanied by the consensus that each power would act in its own zone as it saw fit.

Thus were the conditions created for the East Berlin city council to embark on a building program without regard to bourgeois property ownership regulations. Land that had previously been in private hands could now be expropriated. No need to observe the boundaries of the elongated plot of land (Parzelle) marked out by Prussian bureaucrats a couple of centuries earlier, before industrialisation, before Berlin’s metamorphosis into an industrial city, a metropolis. The Socialist state had the power. Henselmann was an East Berlin architect. The projects he developed could not have been built in that way anywhere else, not in the West, not even in West Berlin. They belong to an age that is past and gone.

Henselmann came from das Neue Bauen, a new movement in architectural modernism. However, he never studied at Gropius’ Bauhaus in Dessau. His great role model was the French architect and urban planner, Le Corbusier. And this man, Hermann Henselmann, designed the Hochhaus an der Weberwiese, Strausberger Platz, Frankfurter Tor – buildings that had very little in common with the modern architecture of the time. For this, he was thereafter decried by his colleagues in the West as a traitor to modernism.

A land in ruins, Eastern Germany, received no special treatment from its Soviet occupiers, no Marshall Plan as start-up financing like the West had. It was a country in which the Soviet Union exacted reparations for the destruction visited on its territory by Nazi Germany by ripping up railway tracks, removing locomotives, dismantling entire factories for rebuilding within its own borders. The GDR, a country in which the governing party nevertheless chose the ruined east of Berlin as the location for a grand boulevard. And it was carried out. So the economic power for such a massive mobilization of labour and material must have been there. There was nothing similar, no building projects on any comparable scale, in the west of Germany, that so much wealthier region. Along the Kurfürstendamm in West-Berlin, that glittering promenade, that window on the free world, shanties were thrown up on the cleared bomb sites. Temporary structures that remained in place; the last, on the corner of Uhlandstrasse, a BMW showroom, was only demolished in 1989. It was replaced by a conventional office block of a type found in every provincial West German town – inspiring the thought that possibly, just possibly, the socialist system may be superior to Western capitalism, that planned economy of the free market.

Und Henselmann kriegte Haue

Damit er die Straße baut

Und weil er sie dann gebaut hat

Hat man ihn wieder verhaut

Auch darum heißt das Ding STALINALLEE

Mensch, Junge, versteh und die Zeit ist passé

(Henselmann was knocked around

To make him build the avenue

But then because he built it,

He got knocked around anew.

One reason why it’s called STALINALLEE

Don’t you see? Those times are away.)

That was Wolf Biermann, in his taunting song Acht Argumente für die Beibehaltung des Namens Stalinallee für die Stalinallee (Eight Arguments for Retaining the Name Stalinallee for Stalinallee). The renaming of Stalinallee as Karl-Marx-Allee, the name it still bears today, was carried out in November 1961 in a cloak-and-dagger act which included taking down the monument to Stalin that stood on the thoroughfare. Biermann, at the time a profuse fount of lyrics and music, must have written his song shortly afterwards. When he performed it to the Havemann family, we found it hilarious. Henselmann and his family would then still have been living on the floor below us in the Haus des Kindes, his own design, on Strausberger Platz. The buildings at Frankfurter Tor had only been completed in 1960, one year before Stalinallee received its new name. Biermann was aware that the story told in his lyrics was not true; Hermann Henselmann was not the architect of Stalinallee. The competition for the urban planning and architectural design of Stalinallee had been won by Egon Hartmann in 1951. He designed part of the street, but went over to the West in 1954. The other designs were by Richard Paulick and Hanns Hopp, both – like Henselmann – rooted in architectural modernism, and by Karl Souradny and Kurt W. Leucht, the latter a former Nazi. Nevertheless, Henselmann was regarded as the architect of Stalinallee not only by Wolf Biermann, but throughout the GDR. This needs an explanation.

Biermann belongs to Havemann; that is well-known. But Havemann belongs to Henselmann, and, vice versa, Hensel- with Havemann. This is not widely known, nor need it be. Henselmann’s wife was my mother’s sister, making Hermann Henselmann my Uncle Hermann. Both families were closely associated for a long time. Both lived in the same building on Strausberger Platz, first in number 9 while the apartment blocks opposite were under construction, then together in the Haus des Kindes. Havemann was on the seventh floor, Henselmann on the floor below. Our windows looked out over the west, over an emptiness that then extended as far as Alexanderplatz, while Henselmann’s faced east onto Stalinallee. The Henselmann family occupied two adjacent apartments with a connecting door, one for the many Henselmann children and the other for the parents. The children’s apartment was chaotic, with old, worn furnishings. The parents’ was elegant and stylish throughout to Uncle Hermann’s design. His office had a raised platform for his great desk from which Uncle Hermann, a small man, looked down on his callers, and a corner seating element for visitors. Then the large salon, in white throughout with plentiful glass, glass-doored bookcases lining the walls and a huge table in the centre with a glass top over white-painted wood, six gigantic – from my childish perspective, at least – and somewhat lumbering armchairs with red upholstery and gold-painted lions’ heads on the arms; a Hermann Henselmann design somewhat reminiscent of a Hollywood movie set. Adjacent was a smaller room, more intimate: my aunt’s room, to which she would regularly invite professors’ wives to take tea. Half-height wooden panelling, mahogany, the rest of the walls clad in elegant green fabric. The chairs, a Hermann Henselmann design, were likewise mahogany and upholstered in the same green fabric. Today I would categorize the interior and its furnishings as art deco. In the family dining-room, a big table with curved cast iron feet and matching chairs, a Hermann Henselmann design. We also had the same table and the same chairs in our own dining-room one floor above, and the ensemble could likewise be found in a cafeteria on the mezzanine floor at the entrance to the children’s store attached to the Haus des Kindes and on the loft floor in the children’s cafe, with its entrance sign ordered by Hermann Henselmann: “Adults must be accompanied by a child.”

Uncle Hermann loved children, or so it seemed to me as a child. His own, however, are left with rather ambivalent memories of their father. He dreamt up horror stories, delivered in instalments over a series of summer evenings. Our two families remained close even in Grünheide Alt-Buchhorst, occupying two adjacent plots there on Möllensee, separated by lilac bushes and with opportunities to slip through from one to the other without having to go round by road. Uncle Hermann invented games for us children at the communal family parties. Henselmann: seven children, Havemann: four, and the swarm of children expected him to entertain them. Henselmann also enjoyed hiking; after all, he had been a member of the Wandervogel youth movement. We hiked along with him, always on the move in a large group. During these hikes Henselmann would spit, loudly and prominently, directing his phlegm onto the sandy path. I was very impressed; no other adult behaved in this way. Henselmann was unconventional, witty, spontaneous, a man of many ideas, inspiring, full of vitality. As I only discovered years later after spending my childhood with him, he used to take uppers; his confusion of the then so drab GDR with an exciting form of socialism may have been under their influence. Perhaps he had taken perverse Pervitin, which had helped to turn German Wehrmacht soldiers into monsters. Or maybe a newer cocktail of drugs, a kind of speed, obtained in the West where it could be bought over the counter in pharmacies. The class enemy had thus contributed to the rise of Socialism by kindling associations of ideas in the brain of our greatest Socialist architect: Hermann Henselmann.

In a nutshell: I was very fond of him. I was proud of him, too, proud of our Stalinallee; I never saw anything comparable on my visits to West Berlin. Because of that, I was convinced that the East was vastly superior. And I was naturally very proud when my uncle predicted a future career for me as an architect on the basis of some talent I showed for drawing, and began to encourage me with the intention of turning me into an architect. For two years, I had to visit him every Thursday in the dome of the tower block at Frankfurter Tor where he had his studio, his architect’s office with several considerably younger employees, who received this small boy with kindness. The buildings at Frankfurter Tor were completed in 1960. I was nine years old. Just one year later, in 1961, construction began on the Haus des Lehrers on Alexanderplatz. It was completed in 1964, when I was twelve, and we were together on the construction site, in the tower and in the Kongresshalle. The shell of the tower was finished; work on the Kongresshalle had progressed as far as the interior. And I had already experienced my first disappointment in Uncle Hermann. He had told me that I was to be the one to design the frieze running around the building, later dubbed the “Bauchbinde” (cummerbund/abdominal bandage) by flippant Berliners; I assume that must have been right at the start of his plans for the Haus des Lehrers, so I was probably nine years old at the time. I believed him, and was extremely disappointed when Walter Womacka received the commission. Womacka’s 1962 work On the Beach was rammed down the throats of the entire GDR. I was ten. I hated it from the start. And I thought the “Bauchbinde” was dreadful, and have never budged from that opinion.

Today the building, including the frieze by Walter Womacka, is heritage-protected. We have to live with it, and accept the soldier of the National People’s Army and his Kalashnikov. As a nine-year-old, I would not have known what to depict there, let alone ever been able to create any kind of design for these enormous, and enormously long, areas. And yet it would have been better to leave the task to children. The start could have been a painting competition, or taken a collection of children’s drawings as a basis. Beginning with the grotesque figures that characterise children’s first attempts at painting, the face of the moon, the smiling sun; moving on to portraits tackled by higher classes, the stylised houses that all children draw at first, whether they live in a typical house of that kind or not; on to perspective drawings of geometric bodies, buildings and streets; and – why not? – the things students draw in biology class, chemical experiment designs, the structure of our solar system? Everything that need to be captured in images in order to be more fully understood. And the sports grounds, the school garden, the classes, the free periods – the whole universe of the school, laid out over those great areas by an artist’s expert hand. A suitable choice for a House of the Teacher.

But then the Haus des Lehrers is also no longer a house for teachers. The idea of establishing a place of encounter for educators belongs to a bygone age, the lost era of socialism that accorded such importance to education, and accordingly also to teacher training. Few people knew at the time the house was built that Womacka’s frieze concealed a library – in fact, one of the most important education libraries in Europe, containing 650,000 works according to Wikipedia. Books are sensitive to light; paper yellows, hence the frieze. But where did Henselmann get the idea from? There is a precedent: the Central Library of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), built in the 1950s. A vast plain slab without a single window, covered from top to bottom on all sides with mosaics created by Juan O’Gorman, who also designed the building itself. Muted colours, nothing brash, symmetrical shapes that do not clash with the form of the building, a symbolic representation of Mexico’s history. An extremely attractive work, and a kind of façade design that Walter Womacka would have done well to emulate. If only he had, it would never have come to the chaos in his frieze, with so many diagonal lines and triangles, circles sprawling outside the borders. But Womacka sought a more dynamic mood, not the statuary of an ideal society in which every professional group is assigned its place, in which a variety of activities contribute towards the success of the whole. There are plenty of examples of that in the social realism movement of the 1950s. This community of the people was always a dream, and not a particularly realistic one; but the dynamic forms that were so popular in the GDR in the 1960s remained mere decoration. That GDR, the one that fell in 1989, would still exist if it had been a state that gave free rein to productive forces, including humans as a productive force, and encouraged them to develop dynamically. Just 25 years later, the state that had completed the Haus des Lehrers in 1964 was itself finished in 1989 –and with it the need for a house of teachers.

And so I grew up in the Haus des Kindes, the House of Children, on Strausberger Platz, in a building designed by my Uncle Hermann. The first school I attended was directly behind Stalinallee. Stalinallee was the road I took on my way home from school. It also had most of the stores where I first went shopping with our housekeeper, and where I was later sent alone. I had school friends in Stalinallee and visited them there. And when I moved a few years later to the erweiterte Oberschule (extended secondary school) at Frankfurter Tor – designed by my Uncle Hermann – I would walk there along Stalinallee when I felt like it on fine mornings. Towards the sun rising in the east, bathing Stalinallee in its morning rays. An uplifting, yet intimidating spectacle. The feeling of being so tiny, yet belonging to something so great. But then Stalinallee, renamed Karl-Marx-Allee, was extended westwards, and the previous void of Alexanderplatz was transformed into a vast construction site that I could watch from our apartment windows. Impressed, horrified and disappointed; in my mind the prefabricated buildings that went up, in their severe uniformity, were a defeat, an abandonment; we wanted more, our aspirations had been greater before, our ambitions were great. We must have overstepped ourselves. Or perhaps we were lacking a Stalin to press us to undertake such vast projects.

I could hardly have been older than twelve when Uncle Hermann realized I would never be an architect and abruptly ceased his efforts at encouragement. One day he had asked me to design my first house, convinced that I should by then have absorbed enough knowledge of how to do it. But what kind of house? The house I would want to live in later. I went off to create a design, equipped with everything an architect would need, provided by his employees. I happily started to draw happily enough; after all, I actually did know how to draw a building layout. Obviously, I was going to become an architect, so I needed a large room for myself, and it should have a mezzanine level – which I thought was wonderfully chic – from which to look over the layouts and models that would come along. But then I ground to a halt. I was utterly unable to picture whether I would marry, whether I wanted children, a family. After three weeks of futile sketching, Uncle Hermann asked me where my drawing was. I had none. But I was a smart, cheeky lad and answered without hesitating that I could not understand how anyone could design and build houses for people whose lives and needs were unknown. That was the end of my apprenticeship with Uncle Hermann. He did not speak a word to me for years, realizing immediately that a boy who asked such questions would never be an architect. He would be proved right. In 1968, when I had been jailed for protesting against the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops, my mother begged Henselmann to use his connections with top members of the Party and the government to have me released. Henselmann first refused, with the justification that “The boy has no talent.” My aunt began to weep, and three days later I was freed.

Friede in unserem Lande, Friede in unserer Stadt, daß sie den gut behause, der sie erbauet hat.

(Peace in our land, Peace in our town, That it may well house, Him that built it.)

Bertolt Brecht

Henselmann’s first building in East Berlin was the Hochhaus an der Weberwiese, a “high house” or tower block not located directly on the future Stalinallee, but intended as a prototype of the architecture that would be built there. In August 1951 the Politburo of the SED (Socialist Unity Party of Germany), the single ruling party, and the East Berlin council decided to commission the design that Henselmann had produced in collaboration with the architects Richard Paulick and Hanns Hopp. The foundation stone was laid as early as 1 September, and construction began soon after on 12 October. The topping-out ceremony for the completed shell was held on 19 January 1952. The building was finished a little over three months later, on 1 May 1952, and ceremoniously handed over to its future residents. What a pace! But Henselmann had very nearly not received the commission at all. In all innocence, he had produced a design in modernist style. Rudolf Herrnstadt, editor-in-chief of the party newspaper Neues Deutschland, member of the SED Central Committee and holder of candidate-member status of the Politburo – a powerful man – published an article in his paper with the headline So nicht, Genosse Henselmann (This won’t do, Comrade Henselmann), in which he attacked modern architecture as bourgeois, decadent and formalist and wrote that the workers had lived in shacks and deplorable tenements for long enough; in a workers’ state they had the right to live in a palace inspired by national and local architectural traditions, as recommended by the Soviet comrades. In other words, in a classicist, Schinkelesque style.

Henselmann would later recount the story, including to me, thus: after the Neues Deutschland article he roamed through the city, through shattered East Berlin, in utter despair; after the rejection of his design for the Hochhaus an der Weberwiese, he had been confronted by the dilemma of either abandoning his convictions or going over to the West. It should be noted here that the West also took quite some time to embrace modern architecture in the post-war period. Moving to the West was thus anything but an enticing prospect for Henselmann. As Henselmann told it, he then went to Brecht, whom he knew and admired; to Bertolt Brecht, the poet and playwright, who had himself been the target of criticism for the plays he staged at the newly founded Berliner Ensemble, who tried to finesse his way through the debate over formalism whipped up by the party. As Henselmann reported, Brecht had told him the most important thing was to establish contact with the new commissioning body – that is, the proletariat, in the shape of the Party functionaries, and to stay in East Berlin to re-educate them. It was no wonder, explained Brecht, that those representatives of the working class had no education since it had been deliberately withheld from them, had no other taste than that of the petty bourgeois. For Henselmann, this vote by Brecht tipped the balance. Eight days later, he submitted a new design for the Hochhaus an der Weberwiese, now embellished in the way that he believed was desired by the Party. His design was received with enthusiasm, and construction began immediately. Brecht was also said to have liked the building. Henselmann pressured him to write the words on peace that were then carved into the black marble of the entrance. That black marble came from Carinhall, Hermann Göring’s country estate in Schorfheide. One might have said “repurposed” if the entrance had not been so very reminiscent of a tomb, had not been so little in keeping with the building as a whole.

An architectural commission, said architect Bruno Taut quite rightly, must be drawn up by the client who commissions it, not the architect who executes it. Except that today’s commissioning clients are generally completely overwhelmed by the task, or at least by anything that goes beyond the decision to build so and so many square metres of apartments, preferably on greenfield sites, or office space. And particularly where the commission is intended as something special, and often enough the commissioner is not the user of the planned building and has no concept of what will be needed to ensure it works properly. An up-and-coming town wants a theatre as a feather in its urban cap – oh, but a concert hall would be good too, and wouldn’t it be even better if it could serve as a handball court as well? So the town gets a multi-functional building where nothing actually functions. The town council wants a museum, but the councillors themselves never go to museums and have no feeling for art. They confuse a museum with a tourist attraction and get – if they’re smart – a Gehry, a tourist attraction. It fulfils its function as a revenue stream for the town, but not the function of a museum. Rebuilding a palace without nobody around that could live there – no prince, no king – and with no knowledge of what should happen in that palace if there is no court life? Such decadence could only be the sign of a democracy. The principal client with the highest status is no longer the lord, the head of the palace, who has lived and grown up in a palace, is well aware of what a palace needs and now desires a bigger and more magnificent palace. The client is someone more like Walter Ulbricht. And so it was for Henselmann.

The roles had changed. The commissioning client of a building was no longer the one explaining what the building should be like to the person that would execute the building. In a world turned upside down, Henselmann the architect, Comrade Henselmann, sat opposite Walter Ulbricht, also a comrade. Perhaps they used the familiar ‘du’ form, as is customary between comrades. One of them, Henselmann, had the ideas. The other had the power. And plenty of other things to think about in the state he oversaw. And as the head of state and of the Party, as the bureaucrat in chief, he had only a vague recollection of the decision that he himself had helped to make some time ago. Everything took its socialist path, and so the architect once again explained the commission he had been given to fulfil, and Henselmann was eloquent, adding a dash of pathos to the paper words of the bureaucratic draft resolution, the great concepts that could mean this or that. He manipulated the architectural commission in his own interests, the way he understood it and wanted it to be understood. Ulbricht followed his words, Henselmann set the direction, and then asked Comrade Secretary General what kind of solution he envisaged for the architectural brief on the table. Ulbricht came up with some idea, naturally keeping it vague, and Henselmann produced a blank sheet of paper from his pocket with a soft, thick pencil that allowed everything to stay nicely vague. He sketched the outline of something that might roughly, if not fully, align with Ulbricht’s idea, but that far more resembled his own long-prepared draft. The layout was ready, the model was finished, but Henselmann did not confront his client with the result, which could call forth some objection or other. It started with a vague sketch, and then they continued talking, but the idea had to take more concrete form, this or that problem needed to be considered, and Ulbricht contributed his ideas, Henselmann scribbled on the sketch, which was becoming more and more chaotic but closer and closer to his own draft, and by the end he had arrived at precisely the building he wanted and Ulbricht was convinced all the ideas were his own, Henselmann would execute them, and the Party had once again proved itself to be the driving force. The factual level was, given the lack of factual understanding, of secondary importance; the decisions were made on an interpersonal level. Feudal socialism. I cannot say whether Henselmann had cynically analysed the situation thus, or simply grasped it intuitively. But it was the only way.

Henselmann only took a different tack on one occasion: with the Fernsehturm, the television tower. After a years-long battle over its location, with Henselmann arguing for the city centre, as a signal proclaiming the modernity of his GDR. The Party, and with it the state, had had other ideas: an imposing tower, a government building. There were many proposals, many designs, none of which were truly convincing. The all-decisive meeting took place on 14 July 1964; the SED Politburo was sitting, and Henselmann faced the challenge of winning over more than Walter Ulbricht, for whom a vague sketch had sufficed. Henselmann turned up with his model and with precise plans, and hung a photomontage on the wall. Child’s play to create in our modern computer age, but a complex and laborious task at the time. Henselmann had ordered photographs to be taken of his Fernsehturm model and of the square which was, in his view, its rightful location; St Mary’s Church to the left, the Rotes Rathaus – Red City Hall – to the right, and behind it, for keen-eyed observers, a long building that was never actually built, a design by Hermann Henselmann. He then revealed his artistic skill. The photomontage had to be recognizable as such, with the aim of conveying an impression of how things could look to the meagre imaginations of the comrades in the Politburo if the Fernsehturm were at the centre of Berlin. Henselmann added a Wartburg car to his scene, slightly too big, then a couple of passers-by, likewise not quite in perspective, and a young woman wearing sunglasses at the front on the right. She was dressed fashionably, her coat open, and striding purposefully towards the observer. Just as we would wish our young socialist women to be. Optimistic. Henselmann found a model for this figure, assisted by the fashion magazine Sibylle. Every issue featured a whole page by his wife Irene Henselmann, an interior designer by profession, where she gave tips on furnishing apartments in a chic, modern style that was somehow always highly individual. The members of the Politburo might have lacked imagination, but there was one thing they could very well imagine; they asked Henselmann about that young woman, insinuating that he had slept with her. Ulbricht, known to be a prude, was embarrassed. He put a stop to his comrades’ unseemly joshing by asking Henselmann: So, Hermann, do you think it will look good? Which Henselmann, Hermann Henselmann, naturally affirmed, whereupon Ulbricht is said to have replied in his inimitable Saxon accent: Well then, let’s build it. That was my uncle’s version of the story, anyway. Who knows how much truth is in there? A Swiss specialist, architect and city planner Hans Schmidt, was then called in to examine how the Fernsehturm would fit into the cityscape and whether it would be clearly visible from a variety of perspectives. As any Berlin resident can confirm, his investigation was positive. 22 September 1964 saw the final decision over the location for the Fernsehturm, made before a model of the whole city centre into which the tower had been placed. And on that occasion Ulbricht is said to have announced, this time not as hearsay reported by Henselmann, but historically documented and thus presented here in quotation marks: “Nu, Genossen, da sieht man’s ganz genau: Da gehört er hin.” (“Now, comrades, we can see exactly: that’s where it belongs.”)

We should start with a critical analysis of the planning results along Stalinallee to date. For example, I believe the raised, plastic elements and the architectural elements at the Weberwiese are still lacking a convincing connection, with respect both to the treatment of the plastic elements and the upper edging of the tower superstructure.

Thus wrote Henselmann in 1952, with a degree of self-critical reflection that is probably a rare thing among architects. Henselmann was right; the Hochhaus an der Weberwiese was not an unqualified success. In fact, the same could be said of all his Berlin works, all with details that make me shake my head upon closer inspection. Much is too bulky, other parts too slender, or the proportions do not quite work, the Haus des Lehrers is missing a floor or two, and the decoration is particularly fraught with errors of taste – like the wave design under the roof of the Frankfurter Tor; whatever put those waves into his head?

I’ve often wondered, and never come up with an answer. And yet the same happened to many a twentieth-century architect with a yen to add decoration, forced to invent something that was based on nothing other than their own inventiveness. And that was not enough.

Henselmann, dismissed by his architect colleagues in the West as a betrayer of modernism and relegated by the intellectuals and artists in the East to the category of opportunist, reacted to those attacks by identifying wholeheartedly with Stalinist architecture and propagating it, at least on the surface. Because he filled that role so eloquently, so passionately and yet so charmingly and winningly, he came to be known in the East as the architect of Stalinallee. To anyone more familiar with the material, however, that was obviously wrong. But Henselmann was the architect-in-chief of Berlin; he had to proclaim his support for what was built under his aegis. Henselmann remained true to the order he had received from Brecht: to maintain contact with the new clients, re-educate them and lead them into the fold of modernism. He had won the competition for Frankfurter Tor in 1953 with a design that was still very Stalinist; construction did not begin until 1957, five years later, and the twin-towered ensemble was completed in 1960; the cupola of one tower housed his architect’s office, where he planned the Haus des Lehrers, the first building in the GDR to feature a curtain wall, a modernist design; and where he worked on plans for redesigning the centre of East Berlin to fulfil all the criteria of modern urban planning. His design for the Fernsehturm was created as early as 1959, although construction only began in 1965. Henselmann, an opportunist, but one who made the most of the possibilities opened up by his opportunism in order to return to his own personal cause.

Henselmann was naturally not completely alone in his aims; developments in political and social circumstances were on his side and he was a part of them. At the beginning of the post-war reconstruction phase, the East Berlin city council had decreed that a new-build apartment should cost no more than ten thousand marks. After the completion of Stalinallee, an investigation showed that each apartment there had cost 90 thousand marks. Obviously building in this style was far too expensive; the need for housing was far too great. Stalin, the man who could potentially have demanded a Stalinesque Stalinallee, had died in 1953. De-Stalinization was only completed in 1961, including in the GDR. The Stalin monument on Stalinallee was taken down in a cloak-and-dagger operation in November 1961 and the street was renamed Karl-Marx-Allee. But the internal process of reckoning with Stalin had begun as early as 1956 with Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Khrushchev, confronted with the problem of rapid urbanization throughout the Soviet Union, implemented a move away from the looming magnificence of Stalin-era architecture like Lomonossov University; starting with Moscow, modest four- and five-storey blocks familiarly dubbed Khrushchevka by the people, spread across the country. The old days were gone, and with them the dream of a society without social inequality. Differentiation crept through socialist society, even in the GDR. Heads of the Party and the state moved to the Waldsiedlung, a forested area in Wandlitz; artists and intellectuals – including Henselmann – found villas in Pankow and Grünau, and the proles stayed in the crumbling old blocks until some of them could relocate to Plattenbausiedlungen, estates built from prefabricated concrete slabs on the outskirts; in Berlin, that was Marzahn. Civil servants, Party functionaries, engineers and managers inhabited the new apartments in the city centre. The second construction phase of Karl-Marx-Allee from Strausberger Platz to Alex, planned from the end of the 1950s and built in the 1960s, is classified as postmodernist, including the Haus des Lehrers. Henselmann, then, was not alone. But neither had he remained an opportunist.

Architecture has nothing to do with the various “styles”.

The styles of Louis XIY, XV, XVI or Gothic, are to architecture what a feather is on a woman’s head; it is sometimes pretty, though not always, and never anything more.

So wrote the French architect and urban planner Le Corbusier in Vers une architecture, published in Germany in 1926 as Kommende Baukunst. Le Corbusier was the great idol of the young Hermann Henselmann and influenced him more strongly than the Dessau Bauhaus. Henselmann received his first commission in 1930 at the age of 25. Villa Kenwin, in Montreux on Lake Geneva, was built for an English couple, Kenneth McPherson and Anni Winifred Ellerman, and was located close to Villa Le Lac, designed by Le Corbusier for his parents in 1924. Le Corbusier visited his disciple Henselmann during the construction of Villa Kenwin and praised him, which remained a lifelong source of pride for Henselmann. Le Corbusier’s style occasionally delivered attractive results; today Villa Kenwin is heritage-protected. But the twentieth century was a time of rapid change in architectural style. modernism took a long time to establish itself, repeatedly beaten back. The buildings on Stalinallee, including Henselmann’s designs for Strausberger Platz and Frankfurter Tor, were mocked in the West as “gingerbread style”, an utterly unsuitable characterization given their references to Schinkel and their lack of any of the baroque or classicist influences that were the rule for prestigious architecture of the twentieth century – not only in the Stalin-era Soviet Union, but also in the USA. The cupolas of the two towers at Frankfurter Tor are reminiscent of the Französischer and Deutscher Dom (“French and German Cathedrals”) on Gendarmenmarkt, the work of Gontard. The idea of designing two buildings at the head of a street to create the effect of a gateway was an echo of the likewise domed buildings opposite Charlottenburg Palace. But Stalinallee also incorporated various attributes of modern urban planning: extensive greened areas, a move away from building right up to the street edge, the separated functional areas, the purely residential areas free from factories and offices.

That is the idea behind these buildings: the creative powers of the human mind claim victory over ruins, war and misery. That idea is intended to create its impact by means of pathos that reinforces faith in individual strength and galvanizes the will to act. The writer’s considerations of which architectural images could best convey the idea were coloured by his imaginings of towers framing the square in a very distinct and powerful way. The tower is a symbol of steadfastness, permanence and aspiring power for our people, more than for almost any other.

But while engaged with the planning task, the author was occupied by a further image: that of a gateway. That idea of a gateway arose from his fascination with the idea of translating the concept of the building as a whole into architectural terms and with the overall city planning concept. It is from Strausberger Platz that one enters the centre of the capital city, so that a certain quickening of the emotions when observing the city from this position is certainly necessary. Moreover, the viewer is intended to gain an impression of passing through a gateway and entering the heart of a city that belongs to a socialist society living in peace and freedom. In architectural terms, gates are always symbols of the start of something new. The expression of the concept of a gateway is an important element of Berlin tradition.

Thus wrote Henselmann in 1952 in an article on his design for Strausberger Platz, naturally a very different language from that used by his great idol, Le Corbusier. And no wonder; Comrade Henselmann had to make himself understood by the functionaries of a workers’ party. The Soviet specifications needed to be fulfilled, a link to the national tradition needed to be forged.

The gateway situation reminds me of the theatre, of a stage. While I can immediately grasp the idea of the gateway, it is hardly a commonplace expression. Add in the architectural vision, and it all starts to become extremely confusing.

An image is not a building; a work of imagery – or sculpture – is not a work of construction – or building. Both involve the action of human hands with the assistance of appropriate tools. Creations of the human spirit. And yet one somehow understands, albeit with some uncertainty, the meaning intended for the concept, the supposed meaning of an architectural image. When viewed from afar, a thrusting, tapered tower creates a thoroughly typical silhouette that could be interpreted as a church by an observer somewhat familiar with our history. The three-dimensional nature of the building disappears from this perspective. Now, one could also assign the same silhouette to an utterly banal office building or an even apartment block, a skyscraper seven times as high. With a completely different plasticity, with hundreds of windows, with a glass façade. Seen as a silhouette, a two-dimensional image in the distance, reminiscent of the outline of a sacred building, a church tower. Transferred from that tower to the mundane office multi-storey, the profane apartment block. The shape remains the same; the content changes. Where God and the Holy Spirit once resided is now the residence of the rich, or the malign bureaucratic spirit of a company headquarters.

Assuming the observer has some imagination, two identically shaped buildings located adjacently at sufficient distance from each other may recall a gateway if a road leads between them. With some imagination, we are prepared to waive the need for a connecting piece between the tops of the two buildings, and nevertheless regard them as a kind of gateway despite that gap. The gateway concept would then be the observer’s imagination of a gate. The gateway situation would be understood as a reminder of the experience of passing through a gateway, with the beginnings of something new on the other side. This is so in the case of Strausberger Platz, but it should be noted that things turned out differently from Henselmann’s visions; Strausberger Platz and its twin towers did not become the gateway to the centre of Berlin to the west. Passing through the gateway, one first encounters a wasteland of prefabricated panel houses that could equally be found in Novosibirsk. A comedown instead of an exaltation. Today’s Strausberger Platz, approached from Alex, creates the impression of a gateway, but one leading into Stalinallee.

But despite the necessity of having an eye for the big picture, one must not forget that normal people, if they are not tourists, do not experience their surroundings in primarily architectural terms. They do not stand before a building and gaze at it, but experience the streets, squares and buildings as they pass by.

This wrote Henselmann in 1967. The voice of disenchantment? Of disabusement? Of the dawning of a new realization?

At the end of the 1970s Henselmann, now retired, was able to travel to the West without requiring an invitation from an official institution. We met, he visited me in my studio and praised my pictures. It seems I wasn’t so untalented after all. Then he expressed a wish to visit the Neue Nationalgalerie, designed by Mies van der Rohe, whom he had admired as a young man, as well as the boxy, gleaming gold library directly opposite, the Staatsbibliothek by Hans Scharoun, previously a friend. We met in a large group. My Aunt Isi was there, Henselmann’s wife; my sister, visiting Berlin from Hamburg; a few people whose names I didn’t know – an up-and-coming architect from the West, an architectural historian. I don’t remember their names. Henselmann and his entourage. We had agreed to meet at the gallery. On the way in, Henselmann stopped to point out the meticulously finished stone plinth to us; Mies van der Rohe’s father had been a stonemason, the bar had been set high. Then we went into the gallery and Henselmann spent the whole time talking to his companions. I was surprised, having expected we would take a closer look at the acclaimed building, perhaps with a critical eye. The same happened in Scharoun’s Staatsbibliothek; Henselmann talked. I pointed out the circular apertures cut into the staircase in the centre of the reading room, for which I could see neither point nor purpose. Henselmann’s only comment was that Scharoun had been obsessed with the idea of communication, the idea of people having to communicate constantly at all times and therefore needing to be able to see each other. Then he remarked that visitors to a library seek to communicate with the people that can be found in the books they have written. To me, that seemed to wrap up Scharoun and his library; they were dismissed in passing. He had not grasped the purpose of the building. Later, in the Paris-Bar amid his troop of companions, Henselmann said of the Nationalgalerie: pictures and wall space below, sculpture in the glassed hall above, and both are viewed in a completely different way, but as it proves, there are not enough of them to fill the vast space; it feels empty. Also true, and a point that drives the exhibition curators to despair. I then mentioned to Henselmann that I had been surprised at the way he had looked at both buildings, which he had come to the West specifically to see; how little he had looked, and how little attention he had paid. Henselmann replied that a visit of the kind we had undertaken, the whole situation was completely artificial; that people go to the Nationalgalerie for the art on show there, and to the Staatsbibliothek for the books there; the architecture makes itself apparent only incidentally, its effect is not consciously perceived. As a result, he had accustomed himself to the fact that when he visited a building that interested him, he was occupied with something else and happy to be distracted. But what about the pictoriality of the architecture, which was so important to him? Then the food arrived, and I missed the chance to ask my uncle that question. Only much later did I realize that the answer was so simple; the pictoriality of a building only works from afar, an effect from a distance; otherwise the building needs to fulfil a function. I do not know whether Henselmann would have answered the question in the same way.

In the 1970s and 1980s Henselmann, who had championed modernism in the East, who wanted to put the architecture of Stalinallee behind him, suddenly found himself the target of praise for precisely those works from architects of post-modernism, by Aldo Rossi, who invited him to lecture in Italy, by Philip Johnson, the US celebrity architect, who described Stalinallee as one of the truly great architectural projects of the post-war period. Henselmann’s buildings from the 1950s now accorded him the status of a pioneer of post-modernism, that movement that views tradition not as something to be overcome, but as a source of stylistic elements that can be referenced without needing to fulfil a functional purpose. The styles came around again, as references. Henselmann accepted this late fame with amusement. It is still remarkable how swiftly architectural epochs change, as if they were fashions; yet buildings need to be first planned, then built, a process that takes time. There is so much work involved. The ensemble on Stalinallee with Strausberger Platz, including Frankfurter Tor, were already things of the past shortly after their completion. In fact, the entirety of Stalinallee as it has come down to us could only have been built during an extremely short phase of the GDR’s evolution. The pace of change is dizzying. Buildings are constructed in a style that is already outdated as soon as they are completed. Not even twenty years later, young architects begin to rediscover the style that had until only recently been dismissed as tasteless, bringing it to light again from the store of recently undergone history. Anti-modern becomes postmodern, and suddenly everything is fine. Everything goes, everything is allowed, and the latest craze for … immortality. But there is nobody left to understand the pathos of Henselmann, that a handful of buildings could strengthen his faith in his own strength, galvanize his will to act.

When we examine our old cityscapes and our spaces of communication, our squares, streets and interplay of successive spaces, the most striking aspect about them is their distinctiveness, their uniqueness. This uniqueness is associated with buildings that – as an information theorist would say – represent demographic symbols, as towers and gateways, a certain plasticity of the buildings, fountains and monuments that help to shape the imagery of home and memory.

Thus wrote Henselmann, once again in 1967, and he succeeded, he created buildings in Berlin that imprinted themselves on the memory in all their uniqueness. Iconographic symbols, if you like. And he even created an emblem, a landmark for Berlin: the Fernsehturm, the television tower on Alexanderplatz. Henselmann had fought to build a television tower in the heart of the city centre. He had named it “the tower of signals” but the name failed to catch on; too over-dramatic for a television tower. Nothing remotely similar had ever been debated anywhere else; television towers were only erected on city peripheries. But it was the sphere that made all the difference. No other television tower anywhere in the world featured such a spherical element, housing all the technical equipment a television tower needed in order to be a television tower. Notwithstanding all the legal wrangles over who can lay claim to being the architect of the television tower, the sphere was already part of Henselmann’s first draft for the tower in 1959. The Berlin Television Tower that we all know had its origins in an idea by Henselmann. The names of the other architects involved in the realization of the project have been forgotten. I give them here: Gerhard Kosel, Fritz Dieter, Günter Franke and Werner Neumann.

Nobody invited Henselmann to the opening ceremony of the tower in 1969. Life can be like that.